NGOs and media are on the front lines of holding governments accountable. Both are core pillars of free, fair and informed societies, and the legal system should work to protect them. But at this year’s Trust Conference, we heard time and time again from activists, NGO workers, journalists, newsroom general counsels and others that the law is making it harder, not easier, for them to carry out their work.

They say it is complex and prohibitively expensive to navigate, especially for marginalised communities. They say it is a stone wall, blocking access to public-interest information held by the state. They say it is a guise, deliberately hidden behind to enable retaliation, intimidation and oppression.

What sets Trust Conference apart is that it is a rare occasion each year when key players from across the journalist, legal and non-profit communities can be in the same room. It’s an opportunity to sound the alarm on challenges like these and to swap guidance and strategies on how to push back and stay resilient in the face of mounting challenges.

I was delighted to be a part of the conversations this year, both as speaker and a delegate watching from the audience. Here are my key takeaways.

1. The spread of ‘foreign agent’ legislation is a grave threat to global civic space

At this year’s conference, we had the privilege to hear from Alsu Kurmasheva, a U.S.-Russian journalist with Radio Free Europe, who was detained in May 2023 at Kazan airport whilst travelling to visit her sick mother in Russia. Her passports were seized, and she was charged with allegedly failing to register under the country’s foreign agent law.

I was held in a cold cell for 6 months. There was no hot water. For days, I didn’t even have the energy to get up out of my bunk bed and warm up the water to brush my teeth

The law has origins in a decades-old principle of international law — that every sovereign state has the right to protect itself against malign interference from foreign powers.

But gradually, over time, autocratic leaders have latched on to the fact that this principle can easily be invoked to stigmatise and cut off civil society organisations and independent media from vital sources of funding.

We saw the tactic widely deployed by India and Russia in the early 2010s, targeting NGOs whose work in areas like election monitoring and human rights advocacy were seen as threatening the credibility of the government. In India, for example, thousands of NGOs have seen their license to receive foreign funds revoked after the country’s Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) was adopted in 2010.

Very quickly the spotlight expanded to include independent media as well.

These laws take slightly different forms but typically entail vague restrictions, onerous registration and reporting requirements that seek to drown organisations in paperwork or trip them up, coupled with harsh penalties for “non-compliance” – assets can be frozen, bank accounts closed, and donations or grants cut off. Refusal to comply can result in fines and even prison sentences.

In 2025, copycat laws are now spreading like wildfire.

2. The timing couldn’t be worse.

Many activists, NGOs and independent media are also facing an extraordinary funding crunch, with governments pulling back on crucial foreign aid. International aid fell in 2024 for the first time in 6 years, and it’s likely to drop even more in 2025. At the centre is the dismantling of USAID, sending organisations that rely on it for their funding into a tailspin.

This year’s conference closed with a discussion of the relative merits and limitations of philanthropy’s capability to plug this gap. On the one hand, private funding can offer agility, supporting vital programs and innovative solutions at speed, often in areas that are politically challenging for states to fund. But there are also huge question marks about transparency, accountability and freedom from bias, if and when NGOs become overly reliant on this revenue stream.

Nobody would really argue that philanthropy isn’t undemocratic. If you look at the history of philanthropy, it is rooted in self-interest and it is rooted in political power…There’s a huge question about transparency and accountability. At the same time, its undemocratic nature enables philanthropy to do things that no one else would want to touch.

3. This trend forms part of a wider authoritarian playbook

Foreign agent laws are one example among a growing list of laws, adopted under the guise of protecting national security and financial transparency, that are, in reality, being abused by autocratic governments to stifle dissent.

At the conference we also heard from Randy Shapiro, Global Newsroom Counsel at Bloomberg L.P, who recounted the story of two of the newsroom’s journalists criminally prosecuted under Turkey’s ‘Capital Markets Law’ simply for reporting on a dip in the valuation of the Turkish Lira against the US dollar. This was a law enacted in 2012 to ensure the country’s capital markets operate securely, transparently and efficiently.

Counterterrorism laws were another example cited across numerous panels, again being broadly defined and wilfully misinterpreted to crack down on activists and journalists who challenge the state.

It’s no longer just about laws that we are prepared for. That we are thinking about before we publish, like defamation or privacy. They are now coming from all directions.

4. Far greater multilateral collaboration is needed to push back. In the immediate term, we must support organisations in the crosshairs to build legal resilience

At a macro level, there is evidence to suggest that strategic, multi-level international campaigns — especially if that pressure stems from threats to disrupt foreign investment into the country — may be effective in pushing back against this playbook. Turkey’s draft 2024 foreign agent bill, for example, was subsequently withdrawn for the time being thanks to a coordinated effort from international legal associations, human rights advocacy groups and media freedom organisations.

We need to recognise that a key Achilles heel is economic. Some of the states now contemplating or passing these bills are the same states that are seeking increasing levels of foreign direct investment. There is an inherent tension between on the one hand asking the world to invest in your country and on the other hand attempting to stigmatise that investment. This is not just a theory of mine. We have seen these arguments work in the last couple of years in Hungary and Turkey

This will not happen overnight, however. What steps can NGOs and independent newsrooms facing these tactics take in the immediate term?

For many, sadly, it will require them to move and rebuild their organisations in new jurisdictions. At the conference we heard first-hand from the Foundation’s own Nick Slater on what that process looks like in practice and how we are supporting newsrooms build the legal resilience to undertake it via our Media in Exile programme.

They are setting up in a completely new legal landscape and suddenly face bureaucracy they have never seen before. We help them register as a new entity, make sure they are compliant with copyright, intellectual property, GDPR etc. We see this legal resilience as a key way to counter these foreign agent laws — because if these media can continue to produce independent, high-quality, fact-checked content that reaches audiences in those countries, that’s doing exactly what the state is trying to suppress.

The stakes are clear: without coordinated support from the global philanthropic and legal communities, as well as governments and civil society, we risk losing a generation of independent media outlets and civil society organisations. Strategic legal interventions, including pro bono legal support, innovative funding models, and sustained international collaboration, are crucial to help ensure organisations can not only survive but continue their vital work.

More News

View All

How ‘foreign agent’ laws are silencing independent media

We explore the growing threat of ‘foreign agent’…

Read More

How the MFC Secretariat supports the Media Freedom Coalition to protect independent media at home and abroad

The MFC Secretariat, hosted by the Foundation, was awarded the Cross of Merit from the…

Read More

Statement on the Closure of the Context News Brand

A statement on the Closure of the Context News Brand from…

Read MoreSupporting media and CSOs to curb illicit financial flows across sub-Saharan Africa

We…

Read More

Our impact in 2025: Building resilience in a turbulent year

Our CEO Antonio Zappulla reflects on 2025:…

Read More

Uncovering illicit financial flows: Training that transformed one journalist’s approach to reporting

Find out how training from the Thomson Reuters Foundation transformed Fidelis…

Read More

Legal needs are rising for NGOs amid attacks on civil society and funding cuts, our latest report finds

Our new report finds that legal needs amongst NGOs have risen significantly over the last…

Read More

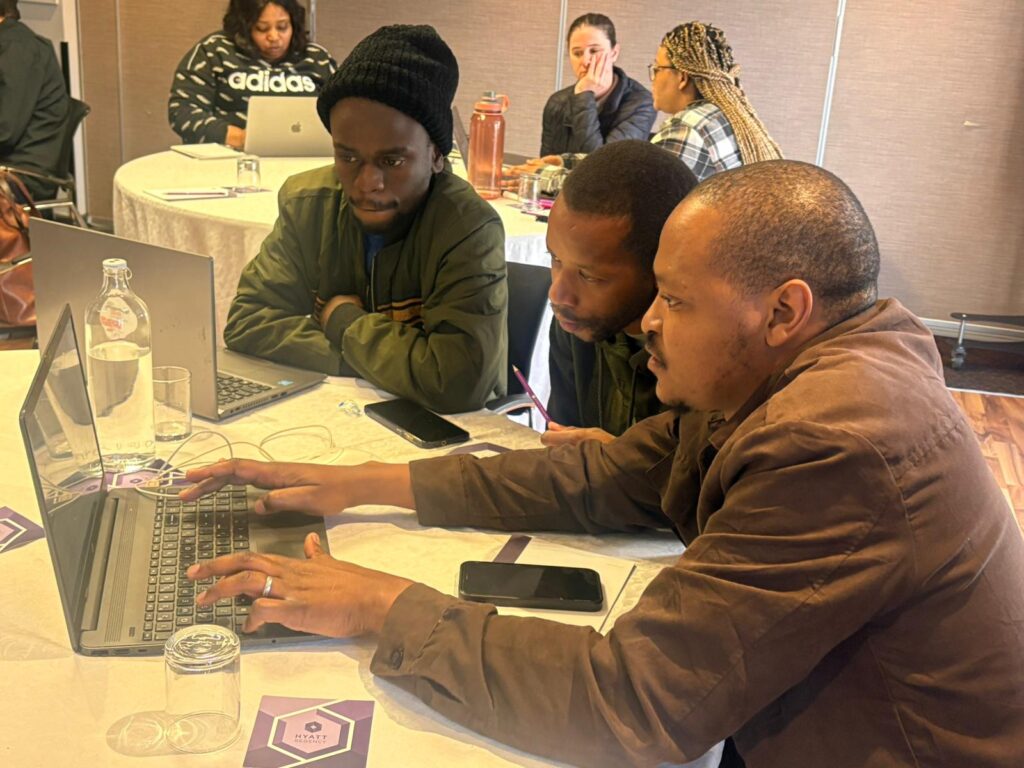

How South African newsrooms are benefiting from strategic and ethical AI adoption

We have…

Read More

World’s largest dataset shows transparency gaps in AI adoption

The Thomson Reuters Foundation…

Read More

Antonio Zappulla: Technology is redefining power, information and influence. What is at stake?

View our CEO Antonio Zappulla’s opening remarks for Day Two of Trust Conference…

Read More

Antonio Zappulla: Three key drivers are reshaping the world and eroding democracy

View our…

Read More